Your Tap Water Meets Legal Standards. But Why Isn't That Enough?

Across North America and Europe, municipal water suppliers work under strict regulatory frameworks to deliver drinking water that is safe, reliable, and compliant. These systems are designed to protect public health at scale, supplying millions of homes every day with water that meets legally defined standards.

Yet even when tap water fully complies with regulations, many households still choose to further treat the water they drink, cook with, and use throughout their homes.

This raises a reasonable question:

If municipal water is legally safe, why is additional filtration so common?

What Are Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs)?

Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) define the highest concentration of specific substances legally permitted in public drinking water. Utilities must comply with national and regional regulations such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) or the EU Drinking Water Directive.

MCLs are established by balancing multiple considerations:

- Known and potential health impacts

- How frequently do contaminants occur in source water

- Available treatment technologies

- Practical limits of large-scale infrastructure

- Cost-effectiveness for the general population

As a result, MCLs do not require water to be contaminant-free. Instead, they define levels considered acceptable for long-term consumption across broad populations, given current scientific understanding and economic constraints.

For reference, examples of regulated limits include:

- Arsenic: 0.010 mg/L

- Lead: 0.015 mg/L (action level)

- Nitrate: 10 mg/L

- Total trihalomethanes (disinfection byproducts): 0.080 mg/L

These values illustrate regulatory intent, not water purity.

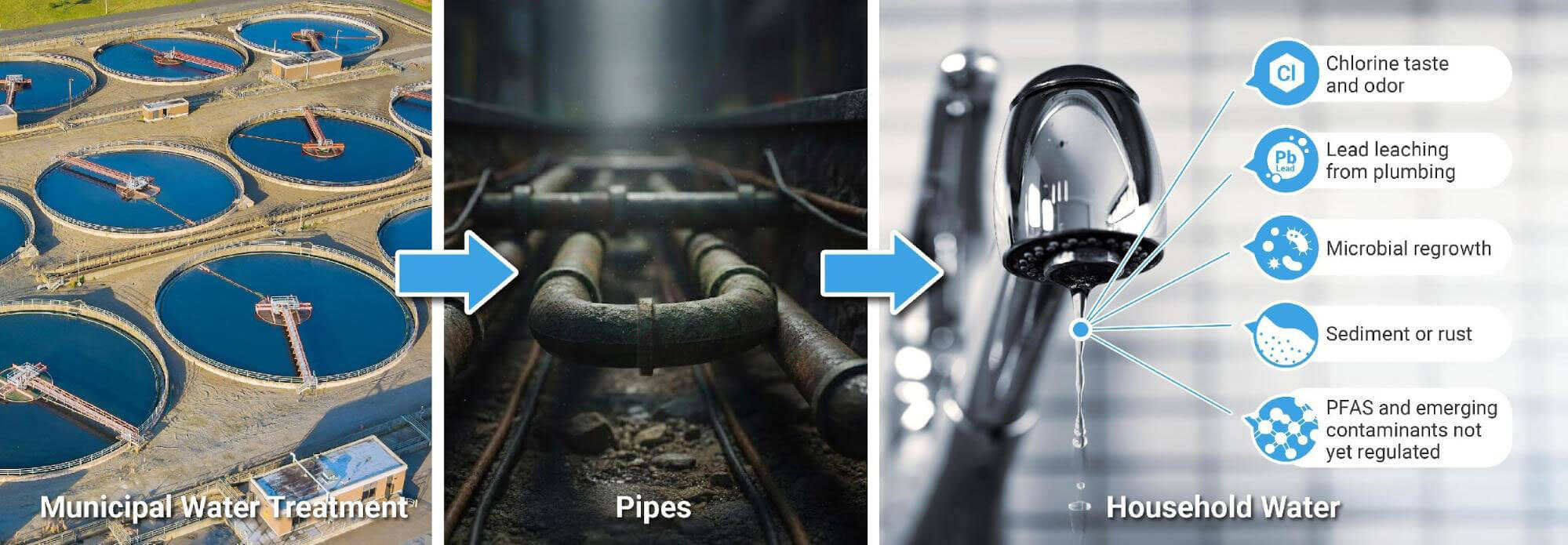

From the Treatment Plant to the Tap: Why Water Quality Can Change

Water may leave a treatment facility meeting all regulatory requirements, but its quality can change as it travels through extensive distribution networks. This reflects two unavoidable realities: the cost of perfection and the complexity of delivery.

Why “Safe” Does Not Mean “Zero Contaminants”

It is technically possible to remove nearly all dissolved and suspended substances from water. However, applying such advanced treatment to millions of gallons per day would require enormous energy input, continuous maintenance, and significantly higher operational costs.

To avoid unsustainable increases in public utility rates, regulatory standards are designed to ensure safety—not laboratory-grade purity. Municipal water is therefore considered safe, but not optimized for taste, aesthetics, or specific household preferences.

The Hidden Variables Inside Distribution Systems

As treated water moves through miles of infrastructure, additional factors can influence quality:

- Residual disinfectants contributing to taste and odor

- Leaching of metals from aging pipes or fixtures

- Sediment and corrosion byproducts

- Microbial regrowth in portions of the network

- Newly regulated or evolving contaminants, such as certain PFAS compounds

These variables help explain why water quality at the tap can differ from conditions at the treatment plant—and why many households seek further refinement at the point of use.

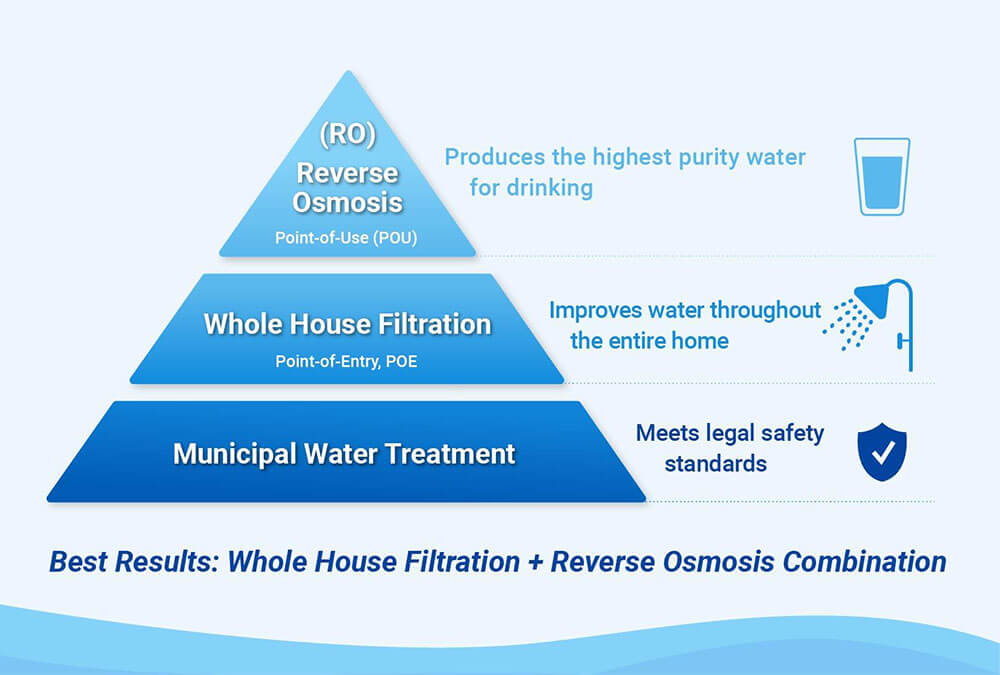

Improving Water Quality Inside the Home

In practice, municipal systems establish a baseline of safety. Additional treatment within the home is used to refine water quality for comfort, appliance protection, and consumption.

Rather than a single solution, water quality is best understood as a layered approach.

Whole-House (POE) Filtration: Improving Water Throughout the Home

Point-of-Entry (POE) systems, commonly known as whole-house water filtration systems, treat water as it enters a building, improving quality at every tap. These systems are commonly used to:

- Reduce sediment, rust, and particulate matter

- Remove chlorine or chloramine to improve taste and odor

- Reduce certain volatile organic compounds (VOCs)

- Protect plumbing, fixtures, and appliances

Whole house water filter enhances water used for bathing, laundry, and cleaning. However, it is not designed to produce the highest purity water required for drinking and food preparation.

Reverse Osmosis (POU): High-Purity Water Where It Matters Most

Point-of-Use (POU) Reverse Osmosis systems focus on drinking and cooking water. Because RO is a slower, membrane-based process, it is typically installed at specific locations such as kitchen sinks or refrigerators.

RO systems can reduce a wide range of dissolved substances, including:

- Nitrates

- Lead, arsenic, and chromium

- Fluoride

- PFAS compounds

- Pesticides and pharmaceutical residues

- Microplastics

- Total Dissolved Solids (TDS)

This makes reverse osmosis the benchmark for high-purity water intended for ingestion.

A Three-Tiered Framework for Water Quality

Water quality is most effectively approached as a three-tier system, with each layer serving a distinct role:

Tier 1: Municipal Treatment

Purpose: Protect public health by meeting regulatory standards.

Tier 2: Whole-House (POE) Filtration

Purpose: Improve water quality throughout the home and protect infrastructure.

Tier 3: Point-of-Use (POU) Reverse Osmosis

Purpose: Produce high-purity water for drinking and food preparation.

When applied together, these layers address safety, usability, and purity without placing unrealistic demands on any single system.

Applying the Framework in Practice

Local water conditions vary significantly by region, source, infrastructure age, and treatment methods. For this reason, filtration strategies are typically adapted to local water quality data and household usage patterns.

This three-tier framework provides a structured way to evaluate options, ask informed questions, and work with qualified water professionals to determine appropriate solutions for specific conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is municipal water safe to drink?

A: Yes. Public water supplies are regulated to meet established health-based standards. “Safe,” however, does not necessarily mean optimized for taste, purity, or household-specific concerns.

Q2: Why don’t utilities remove all contaminants?

A: Achieving near-zero contaminant levels at municipal scale would require disproportionately high costs and energy use, significantly increasing water rates.

Q3: What substances may still be present in treated water?

A: Residual disinfectants, trace metals from plumbing, disinfection byproducts, and other regulated or emerging compounds may be present within allowable limits.

Q4: Why can water quality differ between neighborhoods?

A: Distribution system age, pipe materials, distance from treatment plants, and local conditions can all influence water quality at the tap.

Q5: Do whole-house filters replace reverse osmosis systems?

A: No. Whole-house systems improve general water quality, while reverse osmosis is used specifically for high-purity drinking and cooking water.

Q6: How long do filtration components typically last?

A: Replacement intervals vary based on water conditions and system design. Media-based POE systems commonly require service every 12–24 months, while RO filters and membranes follow different schedules.

Q7: Is this approach applicable to well water?

A: Yes. Private water sources often require tailored treatment for minerals, metals, organic matter, or microbiological concerns, using the same layered evaluation approach.

Final Note

Understanding how municipal treatment, distribution systems, and in-home filtration interact allows for clearer expectations and better long-term decisions. Water quality is not a single choice, but a system—one best evaluated using sound data, realistic goals, and proven frameworks.